The saying goes that a calendar is the most dangerous thing on a cruising sailboat. Maybe the corollary is that expectations are the most limiting. When we headed to Panama toward the end of our time in the Caribbean, I had narrowed the country to two identities: the Guna Yala and the Panama Canal. Both were, of course, phenomenal in their own distinctive ways, but the real surprise came after we’d left both behind and started cruising Panama’s Pacific side.

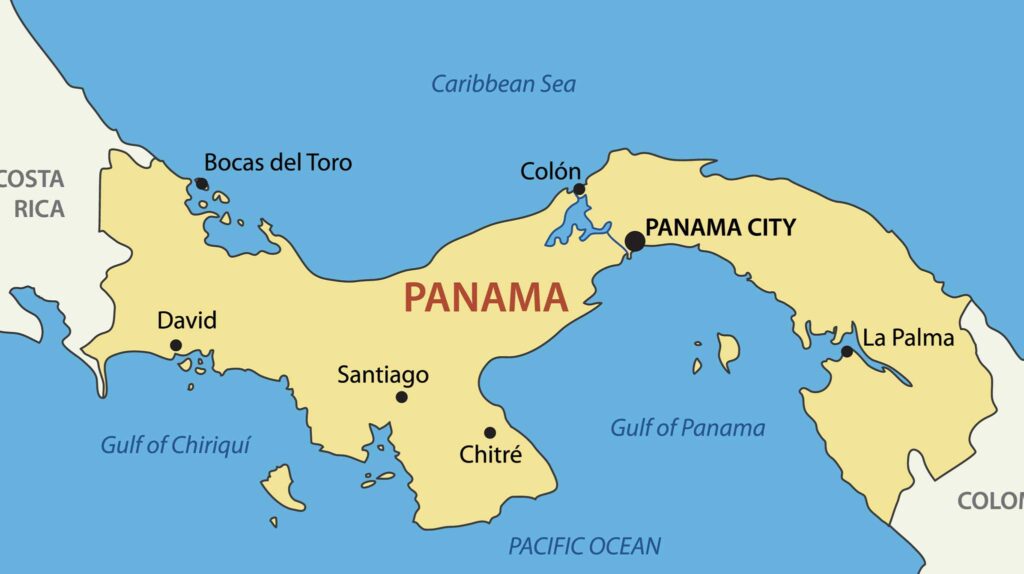

Taboga, Las Perlas, Coiba, Las Secas, not to mention Panama City itself—the list of new names and places just kept growing. In readying myself for this part of our passage into the Pacific, I had missed the obvious. Panama has a rich and fascinating history and a diverse and vibrant present that spans both sides of the country. In my naivety, I’d not realized there was still so much left to see.

Our first stop was Taboga, a small island 5 miles from Panama City and historically a holiday destination for those in need of a weekend respite from the bustle of the big city. During the French and American canal years, foreign diplomats and expatriates would take a short ferry ride over to enjoy the clean water, white sand beaches, and relaxed island vibe. It felt only suitable that we would follow this historical flow to Taboga to enjoy the same pleasures as those who had gone before us.

The small town reminded me of a sleepy Portuguese seaside village, as quaint as it was quiet. Christian shrines lined doorways, curbsides, back-end alleyways, beaches, and rocky outcrops in numbers to match the island’s resident population, denoting an island for the pious. A walk through town took us up winding dirt tracks to views across the sea to Panama City’s dramatic skyline. A walk in the other direction led to a small sand spit crowded with beach umbrellas and stalls selling rum-filled pineapples and spiked coconut concoctions. We enjoyed the quiet, relaxed isolation offered midweek. But on the weekends, that serene atmosphere was obliterated by a pumping party zone to rival Miami Beach on Cinco de Mayo, the statues of sainthood all but forgotten.

The cacophony of competing ghetto blasters, the moving mass of beach bums, and the endless battle for a place in line for a rum cocktail were enough to turn us toward quieter anchorages. We sailed for Las Perlas, a collection of 200 predominately uninhabited islands 50 miles south of Panama City in the Gulf of Panama. The distance brought us to a completely different side of the country—remote, isolated and pristine, weekends included.

Rather than the palm-fringed white sand beaches on the Caribbean side, the islands off Panama’s Pacific coast are covered in dense jungle crowding a shoreline of black sand beaches that offer an unparalleled rugged, wild beauty. This wildness extended to the sea itself, as we sailed through boiling water created by a frenzy of mobula rays with a sky full of swooping seabirds overhead.

As we dropped anchor, a juvenile whale shark swam under our bowsprit, and moments later we were in the water swimming alongside this gentle giant, the most memorable welcome to the beautiful Pearl Islands. We’d come at the right time, as the bloom of plankton filling the bay drew the megafauna that depends upon them for food, such as humpback whales, whale sharks, and rays. We spent our days in the water surrounded by large schools of mobula and cownose rays and the solitary whale shark or humpback that swam with them, our bodies wrapped up in the middle of their feeding frenzy, their dizzying speed and aerodynamic displays an amazing force to behold.

When we finally turned our attention away from the sea, an equivalent but different beauty ashore was equally stunning. A copse of dead trees nestled into the dense jungle lining the beachfront provided a perfect nook for a large flock of resident macaws. Their bright red, yellow, and blue feathers were a brilliant shock of color against the bleached wood they were perched upon. Below, a thick cluster of cormorants blackened the beach. While we were there, we were the only humans amid this rich pageant of wildlife. These islands were, without a doubt, true to their name: the Pearls of Panama.

It was near impossible to pull ourselves away from our secluded oasis and our indulgent self-sought isolation, but a cruising boat is always on a timeframe and it was time to move on. We set our sights on Coiba Island, the largest island in Central America.

Coiba fascinated us with its dark history. It had been a penal colony, akin to America’s Alcatraz or South Africa’s Robben Island, where the hardest criminals were subdued between 1919 to 2004, a place of such harsh conditions that the guards of the time locked themselves in at night to stay safe, rather than the other way around. Before that period, the island’s last known inhabitants had been removed in the 1500s, leaving the island completely untouched by human interference for 700 years.

Coiba is now an uninhabited marine reserve, having been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005. With a scatter of buildings left to ruin and access limited, the island and the ecosystem within and surrounding it holds some of the greatest biological diversity in the world. Going ashore is off limits to visitors, so we spent our time exploring its impressive biodiversity at depth. The coral reef is the second largest in the eastern Pacific and supports a rich underwater biodiversity, and our dives brought us in close proximity to white-tip and hammerhead sharks, eagle and devil rays, turtles, and schools of jack, snapper, and the illusive marlin. Coiba is the Galápagos of Central America’s underwater world and, true to reputation, has the best diving that Panama has to offer.

We continued north of Coiba to the small archipelago of Islas Secas with the best intentions of continuing our exploration of the Gulf of Chiriquí’s rich marine environment, but we were drawn to the raw, untouched natural beauty above the sea instead. Of the 14 volcanic islands that make up this small island group, only one has been turned into a luxury 24-guest eco-adventure resort. Other than this single development, this small cluster of islands has been left uninhabited for over 600 years, allowing for the preservation of some of the most pristine conditions ashore and under water.

We stayed clear of the exclusive resort and visited a few of the smaller islets, enjoying the complete solitude. The soft rustle of dense, green bush and slow lap of rolling water was the only outside sound in our small universe, other than the occasional rumble of a passing fishing boat. Outside this periodic and distant disruption, the tranquility inside this serene, remote setting was absolute. We matched the pace of our days to nature’s slow, gentle melody and enjoyed the feeling that Las Secas was ours, and ours alone.

As we wound up our cruise through Panama’s Pacific islands, we grasped how extraordinary this corner of the world truly is. The adventures we’d had far surpassed our ability to count them on our collective fingers and toes. Our time in country was closing down, and we decided to pull out of our isolation and serenity to head for chaos and noise. We needed to move for practical reasons, such as provisioning and clearance, as well as for personal reasons, and there was nowhere in Central America better suited to this than the bustle of Panama City.

Panama City was a relatively low-key central hub until the early 2000s when a development boom started transforming the older colonial homes into larger multistory houses and high-rise condominiums. Trouble in the Middle East and strain on shipping through the Suez Canal led to an increased demand on the Panama Canal and port facilities in Balboa. As a result of the influx of shipping and trade and the resulting multibillion dollar expansion of the canal, development boomed and the city expanded into what it is today—a vibrant “two-in-one” city that offers a perfect blend of quaint-old and glittery-new.

Depending on where you are in the city, it can feel like you are either standing in the center of a mini-Dubai or looking down the tunnel of time at a centuries-old seaside fishing village. The financial district, or Area Bancária, is built-up and gleaming, with skyscrapers crowding the skyline and the billowing puff and honk of a thousand cars jammed into a square-mile block. The area is filled with modern office towers and banks, high-end hotels, fancy restaurants, and name-brand retail stores.

Casco Viejo, on the other hand, is in the historic district and offers a quaint pedestrian-only area filled with winding cobblestone streets flanked by 1600s buildings turned trinket shops. Throughout the old quarter are sprawling plazas surrounded by numerous museums and churches open to tourists throughout the day. We spent time wandering around the streets of the historic district, enjoying the bustle of activity. We spent hours getting history lessons on the building of the Panama Canal, of life during the Spanish colonial period, and the impact of gold and money to the region. Our evenings were less educational but equally valuable, as we sipped margaritas on barstools in draughty rooftop bars and ate some of the the juiciest carne asada from the best restaurants in the city. We filled our time dancing between the new and the old, our days a flurry of activity that was juxtaposed to our relaxed Gulf of Chiriquí experience.

When it was finally time to leave and head across the Pacific, I reflected on how much more there was to Panama than what I had expected—and I imagine most cruisers expect—that it’s little more than a direct route from the Atlantic to the Pacific, a conduit for the adventure in one ocean to the adventure that lies ahead in the next. Instead, I learned that the Pacific side of Panama is a rich destination in itself. The two sides of the country are dramatically different from each other, yet equally rewarding.

May 2025