“You will be all right, my child.”

The words came from a place she didn’t know. They didn’t so much come into her consciousness as flow through her whole being. She thought: “Is that God?”

And then Lindsay Smith waited for something unknowable, slumped on the pavement outside the Doyle Sails loft in Salem, Massachusetts, while the man who had shot her three times in the head and left her for dead moved off and killed himself. She heard the sound of violins, which she only realized later were sirens.

• • •

This story could—and does—happen anywhere. People make mistakes. Domestic violence is too insidious, overwhelming, and shameful to reveal. Guns are a dime a dozen. Courts make decisions based on laws that are less about protecting victims of abuse than requiring them to prove—within the narrow confines of the language of law—why they fear for their lives. Like a bullet splintering bone into a million irretrievable shards, lives shatter in an instant, smithereened into something altogether darker.

That this story happened to one of the more notable sailing families in one of the East Coast’s more prominent sailing communities shouldn’t come as a shock. But it did, and it still does, and though every day since that day, November 15, 2021, has been literally one foot in front of the other, it is the support of that community and the strength and spirit of the woman they have gathered to stand behind that take this story beyond the darkness.

Although if you ask Lindsay, she does not, in her wry way, see herself as strong.

“I don’t think I’m actually strong at all. My entire story is just enduring pain and doing what people who are smarter than me tell me to do.” Quite often, she says, she has thought about giving up. “I think in circles to myself, what is there to give up on, what does that even look like? Then, if I’m thinking negative at all I just come back to how far I’ve come, and it makes me want to continue to get better. I look at the wheelchair that’s now in the corner of the room just as a seat to sit on sometimes. Not a necessity. That’s how I have to do it: ‘Well, look at this progress I have made so far.’ ” And, she adds, “I have a lot of positive people around me.”

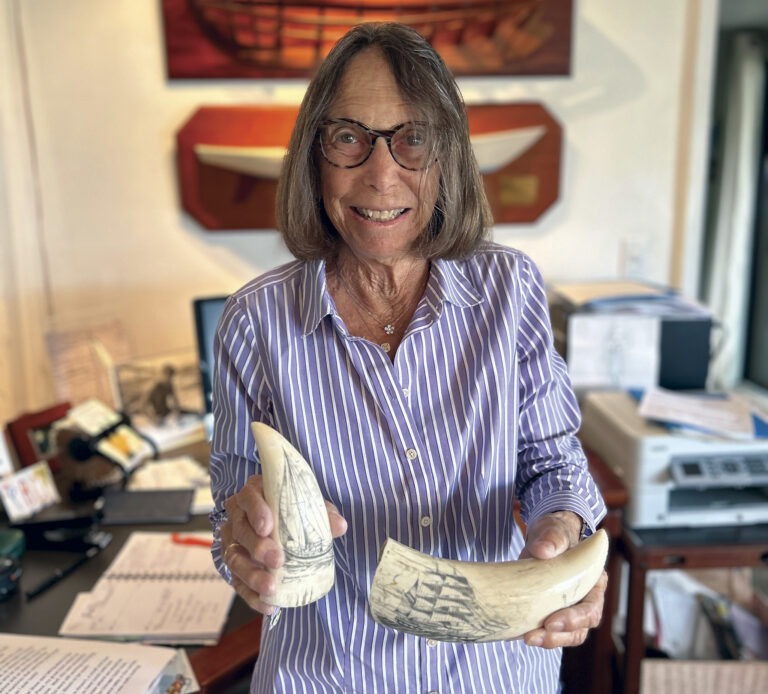

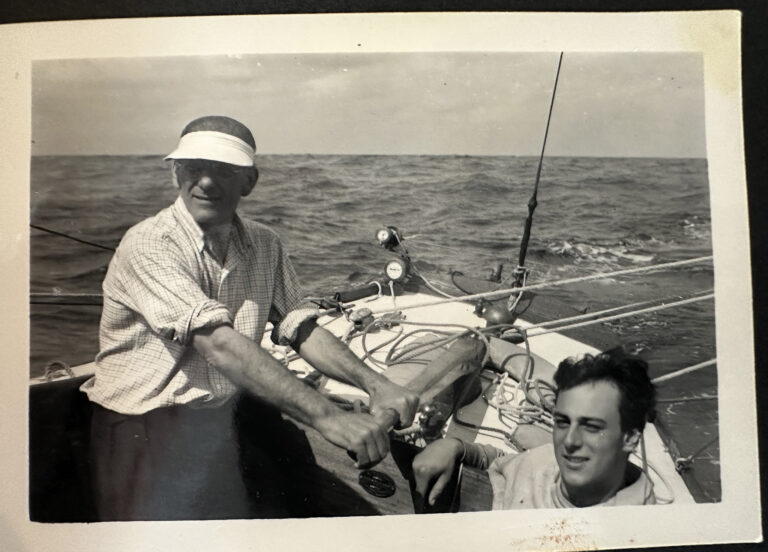

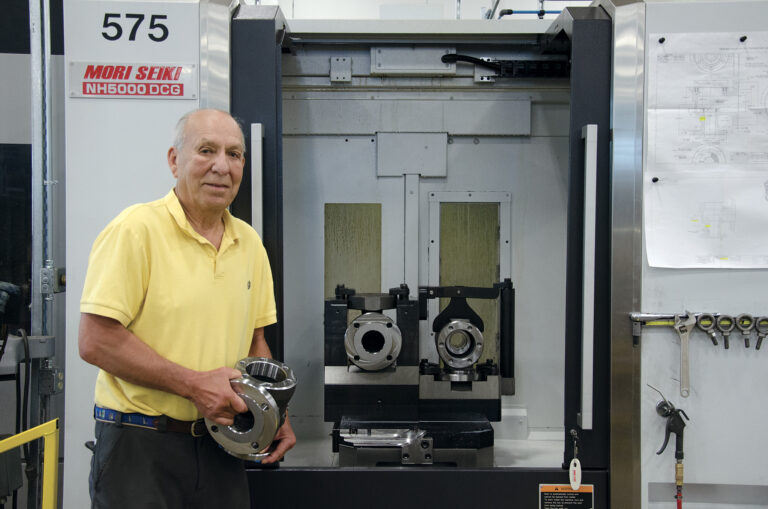

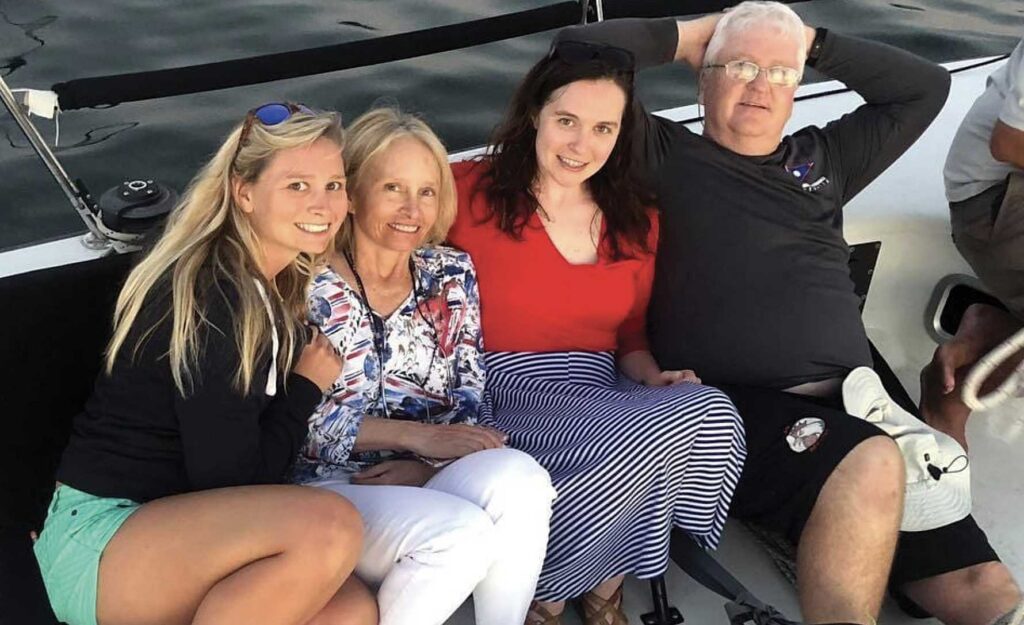

“The most impressive thing is that Lindsay’s attitude remains quite good through the whole thing,” says her father, Jud Smith, chief of Doyle’s One Design loft in Salem, two-time Rolex Yachtsman of the Year, and 10-time world champion in multiple classes of boats, including the J/70 (twice) and Etchells. “She knows exactly what happened, she understands all that, but she doesn’t seem to let it get her down. Her attitude is remarkably good. I don’t know how she does it, really.”

“She’s a fiercely independent person. She’s really funny. The amount of adversity and how far she’s come, every year, it’s just amazing,” says Sarah Brophy, one of Lindsay’s teammates aboard the Etchells Fast Mermaid. “For me, I also really value the power of the sailing community and how it can lift you up and really give you support in ways you didn’t know…I feel like the sailing community views her as a family member and would do whatever they could to protect her and rally around her.”

• • •

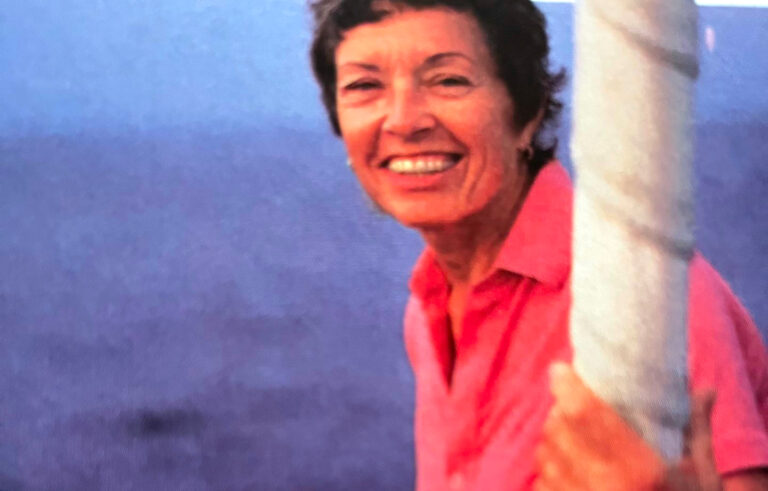

On November 15, 2021, Lindsay was general manager of the Doyle Sails loft in Salem. At 33 years old, she was immersed in the racing community in Marblehead where she’d grown up as the daughter of well-known sailors Jud and Cindy Smith. Earlier that year, in June she’d been spinnaker trimmer aboard the Etchells Fast Mermaid, racing in the class national championship in Marblehead as part of an all-women’s team sponsored by local sailor Jay Watt. The team’s logo, which she helped create, was a voluptuous mermaid, especially eye-catching against the boat’s hot-pink spinnaker.

Outwardly vivacious, with a streak of wild child and known for her sly, quick humor, Lindsay had also by then been in a relationship with Richard Lorman, who was 55, for about five years. They lived together in the house she owned in Hampton, New Hampshire. But there had been violence and coercion in the relationship as early as 2016, according to court documents.

“I was in a bad domestic situation, and I didn’t see the red flags,” Lindsay says. “When everything is horrible you don’t want to tell people. You do everything you can to not tell people, because there’s a shame attached to it.”

By early September 2021, she could no longer hide her fear. She left the house, staying off and on with friends and her parents, who hadn’t known what she’d been going through.

“She tells us, lets it all out, ‘I’m in big trouble, I’ve been seeing this guy, he’s been at my house, and I want to break it off,’ and the guy was not taking it well,” Cindy Smith says. “And he was calling her work, her sister, her sister’s husband, Jud, and saying terrible things, trashing her. And he was a gun guy. We’re not gun people, don’t know anything about them really. But he was into them.”

On September 6, using a tracking app on her phone, Lorman found out Lindsay was in Marblehead and demanded to meet. She agreed but only if they met in a public place, at a park by the Marblehead Lighthouse. He showed her “a pile of guns” in his truck. According to court documents, “At the park, R.L. yelled profanities at L.S. …stating ‘I am going to f–k you up. I am going to f–k up your whole life. Everything you hold dear, I will f–k it up. You can’t trust anything to be okay anymore. I am going to turn your world upside down. You’ll see. You’ll pay. You chose this.’ ’’

At the advice of Hampton police, Lindsay in mid-September sought and won a 30-day temporary restraining order against Lorman. But at an October hearing to make the order permanent, in the 10th Circuit Court, Hampton Family Division, Judge Polly Hall denied a “final Domestic Violence Order of Protection in the matter of L.S. v. R.L.,” stating that the court could not make a finding of “abuse” as defined in applicable state law, and that it “could not find that the defendant posed a present credible threat to the plaintiff.”

Shortly after, says her Fast Mermaid teammate and friend Casey Williams, the two went out to dinner where Lindsay described her shock at the court’s decision. “She said to me, ‘There’s not much I can do about it now, he’s probably just going to come shoot me,’ ’’ Casey says. “I don’t know that a restraining order would have stopped what happened, but she had to live with that heightened fear because of it.”

Late afternoon of November 15, Lindsay finished her workday at Doyle and exited the northeast side of the warehouse building through a door belonging to an adjacent gymnastics business. It was already dark, and a U-Haul type van sat in the narrow parking lot against a dense cluster of trees, about 20 steps away. Witnesses later said it had been there much of the day.

“He waited outside my work and then he approached me to have an argument about something, who knows, and he was yelling, and then he tasered me,” Lindsay says. “And then I guess he dragged me to the U-Haul. People thought he was going to kidnap me.” She saw a woman who was picking up her kid from the gym and screamed at her to call the police, that he would kill her. “The gym people called 911 and pulled everyone back in and locked the door.”

“When he tasered me I fell to my knees, I was on my knees begging him not to kill me, and I said I would do anything, because it had worked before to get him to stop, and I figured it would work, and then he shot me in the face, basically. Three bullets ended up in my skull.” Three rounds jammed in the gun, “so the casings just fell to the ground, which is a horrible sound I still hear when I drop things.”

Lying crumpled by the van, the voice came through her: You will be all right, my child.

“That still haunts me, but in a good way,” she says. “What haunts me in a bad way is how his eyes went from blue to black just before he shot me. Like he had to die inside before he could kill someone.”

• • •

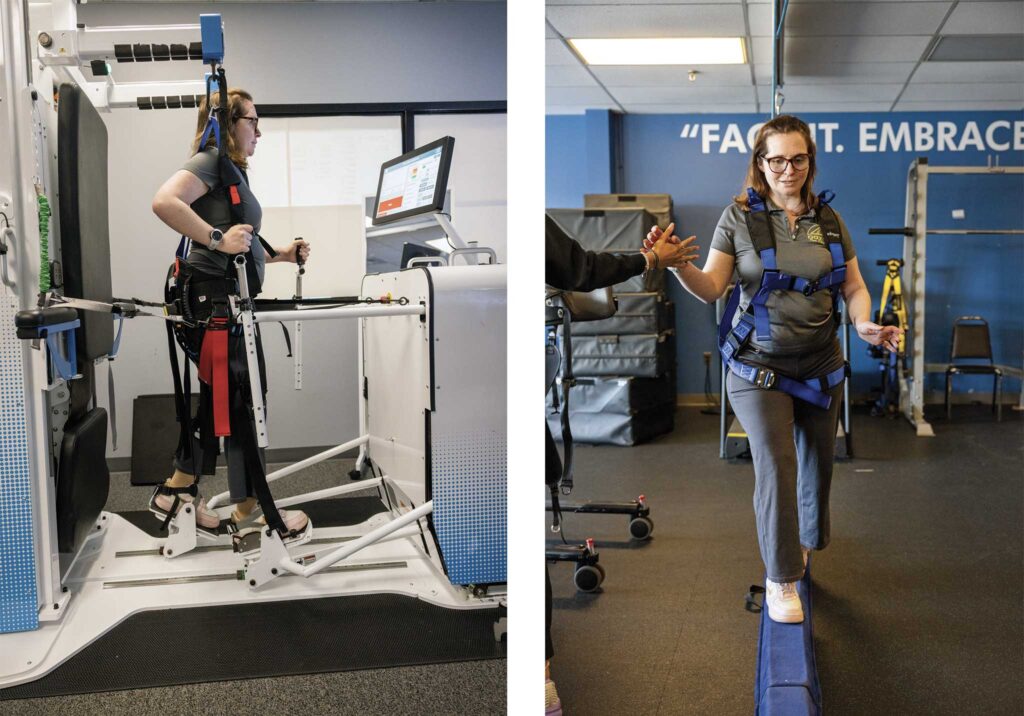

Inside Project Walk Boston in Stratham, New Hampshire, ’70s and ’80s rock is pumping. Across the top of one wall painted in tall letters: “Face It. Embrace It. Defy It. Conquer It.” Throughout the room, fit and focused physical therapists help a variety of people who are struggling to retrain their brains and bodies to master the meticulous mechanics of what so many of us take for granted. The ability to take a step. To hold one’s head up. To hold a toothbrush. To hold anything.

It’s early April 2025, and it has taken an hour to drive here from the Doyle loft in Salem, where Lindsay is back to working 30 hours a week alongside her father in One Design, managing purchase orders, taking calls from customers, and otherwise helping keep things running. She makes the trip to Project Walk twice a week (it was three times a week initially), riding with her devoted boyfriend, Kenny Harvey, or her Aunt Tammy, who is still her “personal care aid,” or her mom, or—if no one’s available to take her—Uber. She can’t drive, because the traumatic brain injury symptom of inattention makes it unsafe, as does impaired peripheral vision in her left eye. She misses the autonomy of driving a car, much as she once missed the ability to walk.

She first arrived here December 27, 2022, gaunt, weak, and in a wheelchair. To get to that point she and her family, friends, and medical team endured a hellish physical and emotional roller coaster, bringing her back from the brink more than once. In a hospital bed for over a year, on a feeding tube for months, she ultimately underwent 10 surgeries.

The night of the shooting, Jud says, the ER doctor at Salem Hospital was a Vietnam vet who had seen similar injuries in war and med-evaced Lindsay immediately to Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, where a neurosurgeon was on staff. In the helo, Lindsay remembers the medics forcing her to stay awake, to stay alive, telling her to look at the lights of Boston. Once Jud and Cindy arrived, “We went to visit this team, and they were discussing their options. It was a lot of heads down in that meeting…they went through, ‘If she survives, how would life look after that?’…She died a couple of times on the table. If it wasn’t for the anesthesiologist who brought her back twice on the table, she would have died.”

That she wouldn’t make it, he said, was unthinkable. “It did occur to me, but it didn’t last long.”

It was not only the brain trauma the doctors had to contend with; the bleeding had caused a stroke. Despite placing a shunt to drain excess fluid from her brain, fluctuating fluid levels caused abrupt cognitive changes; one day she would be doing fairly well, the next she wouldn’t know where she was, Jud says. And yet, Lindsay defied all odds, slowly improving.

“Until July, she had part of her skull removed [to cope with brain swelling], she had a helmet on the whole time,” Cindy says. Then, after doctors replaced the missing skull section with an implant, she grew terribly sick. “Within three days she was the worst I have seen her. She got many infections—meningitis, encephalitis, then she got Covid, then she got pneumonia, she had it all at once and for months.”

By October, Cindy says, the medical teams were out of options and had recommended palliative care. Lindsay was wasting away, sleeping endlessly, unable to fight off this latest assault.

“That was very, very hard,” Cindy says. “She wasn’t going to make it because they couldn’t figure out what the meningitis was caused from and why she was sleeping so much.” The family had gathered and she was close to death again when her neurosurgeon, Dr. Rafael Vega (Lindsay calls him her archangel), suggested one more surgery to place a second shunt.

“They described it as a Hail Mary, and it was,” Jud says. “What was amazing is when they put the second shunt in how well she recovered.” She was out of the hospital in a week and a half.

By the end of that year, 2022, she started with Project Walk Boston, a place that has been instrumental in her recovery.

“Project Walk takes it to a new level—‘Oh, no, we’ll get you walking. You’re not done.’ ’’ Jud says. “They don’t accept the fact that you get injured, and this is what it is for the rest of your life.”

Lindsay has already run through an hour of work when trainer Morgan Frost puts a harness around her, attaches it with a line to a track in the ceiling, and tosses a 4-inch-wide foam beam on the floor. Then she coaches on form and alignment at each step as Lindsay walks the beam, trying to keep her left ankle—which is in a brace and constantly wants to roll out—under control.

It is intensely focused, hard work, this retraining of muscle and mind. Her ankle and gait are just two elements of Lindsay’s fight to advance. The stroke affected mobility on her left side. She has functional use of her left hand, but fine motor skills remain a struggle.

Every victory, large and small, is celebrated. Leaving behind the wheelchair. Touching a finger to a thumb. Zipping her own jacket. “Never” lays down a challenge. When told Lindsay may never be able to use her left hand, Cindy says, “I said, let’s not say never. We’ll just keep working on it.”

“It is a little frustrating that there is not a direct line to get to my goals. There are so many different things that need to be worked on…there are so many paths to walk,” Lindsay says. “So I have to keep pushing, and I have to push in so many different directions, and it’s a little overwhelming. But whatever I do, put my head to, I just keep pushing and I figure if I do that enough everything will come together.”

Towards the end of the strenuous two-hour session, Kenny shows up and holds her hands through the most painful part. Then he gives her a ride home.

• • •

From a distance and in some cases from very close up, the sailing community based around Marblehead and Boston reeled at the horror of the shooting. Then they took action.

“I think because Lindsay and her sister and Cindy and Jud are all heavily involved in the community themselves, there is a gift that they have given the community, and they’re receiving it back also, because of this time, commitment, and dedication,” says Casey Williams, Lindsay’s Fast Mermaid teammate. “What this terrible incident brought out is there’s a real sense of community, and mariners sense that we’re all in this together and we have to take care of each other so we all survive.”

Within a week, she says, “Kenny and Jay [Watt] were asking me, ‘Do you have the graphic for the mermaid so we can make bumper stickers and try to raise some money?’ That’s a small thing, but that idea of what can we do was nearly immediate.”

The pink stickers popped up everywhere; then Eastern Yacht Club in Marblehead hosted a silent auction as the first fundraiser in May of 2022. In June, the Boston Yacht Club sponsored the first Fast Mermaid Pursuit Race, a one-day regatta to raise money to support Lindsay’s recovery. Project Walk Boston, for example, is completely outside insurance coverage, so everything comes out of pocket. All the funds raised by the regatta have gone to support this, Jud says.

“I just can’t say enough,” Cindy says. “We are forever indebted to our whole community in Marblehead.”

Fast Mermaid quickly became one of the best-attended events in the area, with more than 50 boats in 2023, when Lindsay was back on the racecourse for the first time since the shooting, sailing on her parents’ Tripp 41. In June 2024, the regatta moved to Eastern Yacht Club, and about 40 boats were on the start line.

Though the turnout was a little smaller, Lindsay was elated; it was the first time she was able to sail again with her Fast Mermaid team on the Etchells. They helped her gear up in the team pink (the Fast Mermaid pink is a regatta theme, and the best dressed team gets a special award) and tagged everyone they could—including Jud—with pink glitter on their cheeks.

“I have never felt more the center of attention than surrounded by fellow sailors and my Marblehead community than being able to also participate in my own fundraising race,” Lindsay said afterwards. While the 2024 regatta raised less money than previous races, it was “certainly the most meaningful showcasing my exponential recovery progress resulting from the fundraising of prior years, [and] to be able to show up and sail with my women’s team instead of arriving with a wheelchair or cane.”

This June, Lindsay plans to be on the Fast Mermaid Pursuit Race starting line again in the Etchells (Eastern Yacht Club is again this year’s host), likely racing with Kenny and maybe one additional crew. She’s getting ready to sell the house in Hampton. She hopes to be able to move into her own place, take some of the burden off her parents and aunt. She’s talking with her physical therapists about training for all she still wants to do—ski, hike up a mountain, drive a car.

“Every time something comes up, ‘Oh, you’re never going to be able to do that,’ I think well, all it takes is hard work and I can do that. I can do hard work.”

Summoned by that voice, she is not stopping. You will be all right, my child.

If you or someone you know is in a situation of domestic violence, you can call the National Domestic Violence Hotline at 800-799-SAFE (7233), text START to 88788, or go to the website thehotline.org.

June/July 2025