Ora Kali had pushed hard to get through New York Harbor and the East River to Long Island Sound, and our nerves were jangling after eight hours of listening to the three-cylinder Westerbeke 13 engine pound away. We picked up a municipal mooring in Port Washington, turned the engine off, and in the silence rejoiced that on our first full day of travel we’d escaped New Jersey.

Rejoiced, that is, until I went below and found black swatches on the white liner in the galley. More stains marred the quarter berth and inside surfaces of a food locker. Boat air after motoring often has a tang of diesel to it, but this time the air smelled of soot.

When Tom and I bought Ora Kali, an almost 40-year-old Sabre 30, a month earlier, we knew she had an exhaust problem. The engine compartment was sooty, and the seller had lined up a mechanic to change seals and gaskets on the heat exchanger and exhaust system. But with the pandemic and it being early summer, he couldn’t do the job.

A replacement mechanic showed up without the parts he’d need and said if he opened the system, it might leak worse when he put it back together. Then we’d be in for bigger trouble, and with mechanics and parts hard to come by, we’d be delayed too far into summer.

Will she make it to Maine?

Oh sure, he said. He tightened a few things. You can sail there anyway, right?

Here in sprays of soot was evidence that the problem was very much still with us. I cleaned up the soot and we continued on. Our plan was to take Ora Kali to our new home on Frenchman Bay, across from Mount Desert Island. Offshore would have been quicker, but because she was so new to us, we preferred the inside route on this maiden voyage.

Down below the salon got dingier and dingier even though I cleaned at the end of each day, and we sailed as much as we could, trying not to use the engine except when needing it to get into harbor against a current.

After two weeks, we arrived in Wickford, Rhode Island, amid a midsummer heat wave and tied to a town mooring. In the cooler morning weather, Tom climbed into the cockpit locker that accessed the Westerbeke and started to unwrap fiberglass pipe insulation from the exhaust piping where it emerges from the back of the engine. Doing so uncovered the arrangement of cast iron plumbing elbows and nipples making up Ora Kali’s exhaust elbow.

As he took off a final wrap the bits fell apart in his hands, one part staying attached to the engine, the other weighing down the hose leading to the muffler. Tom emerged looking a bit like Bert, the Mary Poppins chimney sweep, covered in soot and coughing.

The integrity of the engine exhaust was totally breached. It was astounding that the system worked at all, but the tightly wrapped tape had kept the elbow functioning after a fashion. Clearly, we couldn’t go anywhere until it was fixed.

On our Westerbeke 13, as on most recreational marine installations, exhaust includes the hot gases of internal combustion and raw cooling water. The hot gases from the combustion chamber pass into the exhaust system via an exhaust manifold on the engine.

A raw water pump draws water into the boat through a filter, after which it enters the heat exchanger where it is used to cool the fresh water that cools the engine. Then it’s injected into the exhaust system and directed overboard with the hot gases, which it also helps to cool. (This is why, after starting the engine, you should always check to make sure there’s water coming out of the exhaust outlet.)

On Ora Kali, the used raw water is injected into the exhaust system downstream of the plumbing elbows and nipples under the insulation that Tom unwrapped. The exhaust elbow itself is attached by a flange to the manifold and carries only combustion gases. The top of its upside-down U shape is above the boat’s waterline, serving a similar function to an anti-siphon loop in a bilge pump or sewage outflow system to prevent water from back-flowing into the engine.

This is why on Ora Kali we didn’t see any water leaks from the failing elbow, only soot. Injecting downstream of the elbow prevents water from blocking the exhaustion of engine gases. Injecting raw water into the exhaust system also turns it into a “wet exhaust,” which is quieter than a “dry exhaust.”

The hot combustion gases that pass through the exhaust elbow are highly corrosive. Outside inspection, even if it includes unwrapping the pipe insulation, isn’t enough on its own, as by the time corrosion is visible you may find yourself in the position we did on Ora Kali.

Any internal inspection requires that the elbow be removed from the engine. On our boat, this meant unscrewing the nuts securing the flange to studs on the manifold. Between the flange and the manifold is a gasket that should be replaced anytime the joint is opened, or at least every five to seven years. If maintenance is left for a long time, as was obviously the case on Ora Kali, the cast iron surfaces become pitted.

This was a concern of the mechanic who inspected the engine before we left New Jersey; the flange joint could have been the source of the leak, but if the surfaces were badly pitted, replacing it without changing the gasket would make it worse. The mechanic was also worried about breaking one of the studs. Removing the flange and replacing the gasket regularly would ensure this could be checked.

On our Peterson 44 while sailing in the South Pacific, we would have tackled the project with help from other cruisers. In Wickford, we combined forces with a mechanic at Pleasant Street Wharf in the interests of time and muscle power. It was almost two weeks before he could get to us.

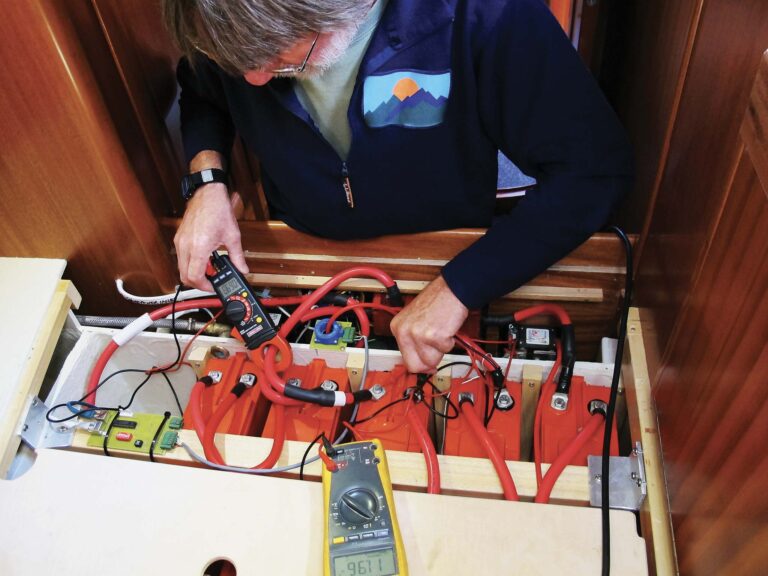

Our job during that time was to obtain a new exhaust elbow. Even on boat-oriented Narragansett Bay this was difficult. For some reason we never resolved, rather than installing a Westerbeke exhaust elbow, either Sabre or a previous owner had fitted their own, perhaps because it was easier to solve the engine room space issues. Finally, we matched it with a mix of galvanized and bronze plumbing parts purchased from Home Depot and online, a gasket and flange sourced from Westerbeke for $200, and bronze barbed hose fittings. One of these barbs would be installed at the new raw water injection point where the hose from the heat exchanger connects to the exhaust system, and the larger one would connect the entire new exhaust elbow to the existing exhaust hose.

Our mechanic was unhappy with the cobbled-together arrangement. He recognized that it fit the cramped space but thought Home Depot parts were inferior and wouldn’t last. Why go to all this trouble to have them rust out? But a plumbing supply salesman (who didn’t carry anything we could use) said there wasn’t anything wrong with the HD parts, and from our perspective, we either used this array and got underway again or we shipped the boat to Maine—not an option we were willing to consider.

After removing the flanged stub of old exhaust elbow from the engine without breaking the studs, the mechanic dry-assembled the parts, wedging himself into the small, sooty engine space to align them in 3D to the gap between engine and muffler. There was surprisingly little pitting around the studs on the engine block, and when he’d sealed the parts together, mated the new flange and gasket to the block, inserted the new pipe fittings into their hoses, and cranked down on the hose clamps, the system was whole again.

A test run of the engine found no soot and no water leaks. Tom covered the new elbow with insulating wrap he found at an auto parts store. The mechanic had recommended Dawn Powerwash to clean soot from surfaces we could reach but suggested we not bother with the engine compartment just yet, where the possibility of shorting out old ad hoc wire connections would be worse than the greasy blackness.

Two days later we left for a test trip to Dutch Harbor on the west side of Conanicut Island in the middle of Narragansett Bay. The engine ran fine, and I kept a close watch on the stream of exhaust water exiting Ora Kali’s transom, as any interruption would indicate the new elbow had failed, but there was no sign of leaks. When we resumed our travels the next day, I felt comfortable running the engine at higher RPMs and for longer periods of time. No more soot, no exhaust smells.

All the talk of inspecting an exhaust elbow should not ignore the elephant in the room; even routine external inspection of the elbow requires removing and replacing insulation. Thermal jackets, like those made by Catalina Yachts for their own models, are in theory easier to remove and replace than insulation wrap, but getting to the straps to pull tight or loosen could be difficult. If stainless steel parts are used instead of cast iron, this may increase the lifetime of an exhaust elbow but doesn’t eliminate the need for routine maintenance.

To make sure exhaust elbow maintenance becomes routine, boatowners should plan in advance what to do if cleaning is needed, how to reinsulate the elbow, and have on hand a new flange gasket as well as any seals that might be needed if you are going to take the inspection farther into the engine side.

August/September 2024