Dinner Key in Coconut Grove, Florida, is sometimes referred to as “The Hotel California”—a place where many cruisers check out but never leave. After almost two months, my wife, Tara, and I started to feel like regulars. We planned on spending the holidays there and had some doctor’s appointments to take care of, all of which extended our stay. After spending a few weeks here last year while getting the boat ready for a trip to the Bahamas, we really started to like the area. However, after two months, we were ready to move on.

One of the drawbacks of this mooring field is that it is exposed to easterly winds, being on the west side of Biscayne Bay. The bay is relatively shallow, and the waves can become very steep, making it uncomfortable for staying aboard. Normally we would move over to Key Biscayne or Virginia Key when strong easterly winds were predicted, but we had one last appointment in Miami to take care of after which we would be free to explore the Lower Florida Keys. Forecasted winds were east 15 to 20 knots, so we knew we would be in for a rough time. But our appointment was for the next day, so we would just have to put up with the bouncing.

The next morning Scout, our Pearson Invicta, was hobby-horsing about wildly. It was so bad that at times the bow was going under the water and bouncing back up with water rushing down the decks. One of our dinghy oars was washed overboard, and the dogs were not allowed on the deck. Worse yet, the updated forecast was saying the winds would be building to 25 to 30 knots with higher gusts! Fortunately, we had doubled our mooring lines, and the moorings at Dinner Key are very secure and inspected often, so we were safe, although it was not much fun.

We have a Honda generator to supplement our solar panels on cloudy days, but I was afraid with the extreme motion of the boat that the generator’s engine could starve for oil. These generators are made to be run on level surfaces, a drawback when used on a boat, so instead I decided to start up the auxiliary engine for an hour to charge the batteries.

The engine cranked over and the starter ran, but then made a “click” sound. I turned it over again, the engine fired and I heard a bang after which the engine stopped. I knew right away something very bad had just happened. Going below I opened the engine cover and found the engine in one piece. This was good. Then I opened the decompression levers and hand cranked the engine using a ratchet. As I did so I saw water coming out of the air intake. This was bad.

I kept trying to turn the engine over using the ratchet with the decompression levers open, but the engine would not turn a full 360 degrees—very bad indeed! Aboard our boat, there is a vented loop on the raw water intake side, but the exhaust has no vent, just a small loop at the transom that travels horizontally and then down below the engine to a wet muffler. My guess was that when the transom rocked into the water, seawater was pushed up and over the loop. Then as the bow rocked forward, the water rushed down to the wet muffler. After 24 hours of this, water eventually got to the engine mixing elbow, came in through the exhaust valves and—bang—we were in trouble. When the engine fired, it tried to compress this same water in one of the cylinders. Although a piston can easily compress a fuel vapor mixture, water just doesn’t compress. This is referred to as “hydrolock.”

Serious damage had clearly been done inside the crankcase. Maybe there was hope for the engine, but I would need to find a mechanic. For the first time since we left our home in Connecticut, we needed help. Worse yet, we knew no one in the Miami area. When faced with so many unknown variables, my mind tends to start thinking along the lines of worse-case scenarios. I figured we would be held up for at least a month and set back many boat bucks—and that would be if everything went well.

As I was engaging in these grim trains of thought, Tara started to do what she does best: managing the problem. First, she made a call to Tom Hale, the technical advisor from our 2014 SAIL Magazine ICW Rally. After agreeing with my diagnosis, Tom suggested that we start with Mastry Engine Center, a local Yanmar dealer (mastry.com). An online search through Mastry provided us with an authorized Yanmar mechanic, Anchor Marine on the Miami River. This company, owned by Mike Bowman, has been in business since 1968. The only problem was that the company was still an unknown to us. However, we needed a mechanic and had few other choices. After we explained our situation to Mike, he said he would need the boat brought to his shop. We explained that we were liveaboards with two dogs. He said we’d figure something out. So on a wing and a prayer, we scheduled a tow with TowBoat US to take us up the Miami River.

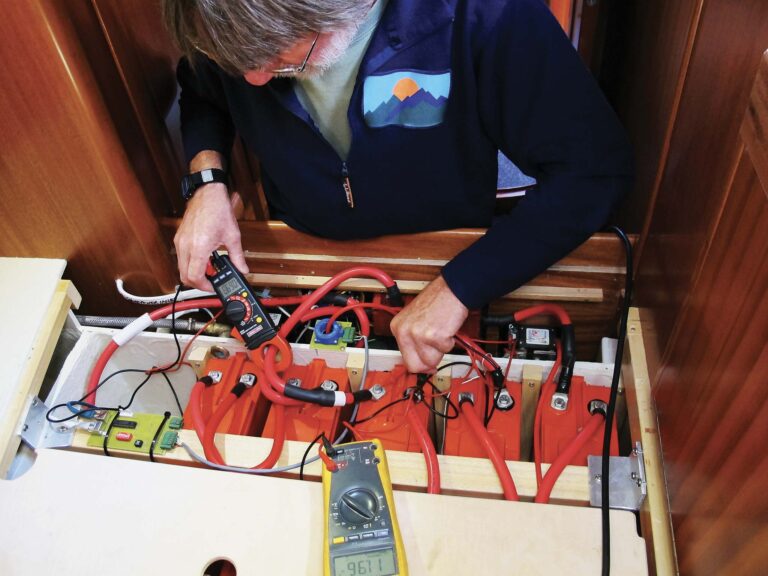

The first good sign we had was when the TowBoat US operator immediately said he knew where Anchor Marine was and that we had picked the best boat shop in the Miami area. We arrived on a Wednesday at 1400, and Mike himself came aboard to look at the engine. After removing the injectors, Mike tried to rotate the engine and after confirming that it would not fully rotate, he looked at me and said the engine needed to be pulled. When I asked if I could do the grunt work of disconnecting/connecting, a smile came to his face and he said not only could I do the work, but he would appreciate it if I did. He said we could stay on board until the job was finished and that we could hook up to power and water at no additional cost. A handshake closed the deal.

Things moved very quickly from there. By Thursday morning the engine was removed using the boat’s boom and a small come-along. By Thursday afternoon, the engine was apart, and it was evident that a bent connecting rod had been the cause of the problem. A new connecting rod, new rings and new bearings were ordered, and by Monday afternoon the engine had been reassembled and bench tested. The engine was dropped into place on Tuesday morning and reconnected by the end of that same day. After a few minor adjustments, it ran better than ever.

After that, the only thing that remained was to come up with a solution to the water intake problem to ensure we never had to go through this kind of experience again. Mike suggested installing a check valve or solenoid valve. But I like to keep things simple, so we installed another loop in the exhaust hose as high and as close to the engine as possible, thus putting it nearly amidships. The waterline changes very little at this point—even in a heavy sea or during a rough night on the hook—ensuring that water will not splash over the loop and therefore into the engine.

Another thing I learned from Mike is that if I had stopped after I heard that first click from the starter, the engine would have been fine. As Mike explained, the starter is not powerful enough to do any damage in a hydrolock situation. When I tried again, the engine fired, providing plenty of power to damage the rod.

All in all, things turned out nowhere as badly as I had originally thought they would, in large part because we were able to find a shop as good as Anchor Marine. Granted, the problem kept us in Miami an extra week, but we met new friends and now know the Miami River area very well. Ultimately, instead of being an ordeal, our hydrolock turned into a positive experience.

Hydrolock Help

Causes of hydrolock and how to prevent it

The most common cause of hydrolock on a marine engine is cranking the engine over with the starter when the engine is not firing. As the engine cranks over, the raw water pump is pushing water through the heat exchanger and into the exhaust/muffler. If the engine is not firing, the water will not be pushed out of the system. Eventually, the water will rise to the exhaust manifold and flow through the exhaust valves and into the cylinder. The easiest way to prevent this from happening is to shut off the raw water intake valve if the engine does not fire after the first couple of tries.

The raw water intake system needs to be looped above the waterline and have an anti-siphon vent. This will prevent water from siphoning into the exhaust system when the engine is shut down.

Another way water can enter the engine and cause a hydrolock situation is through the exhaust outlet through the hull. There are a few different ways to prevent this:

A flapper valve at the outside of the exhaust through-hull would work.

Looping the exhaust hose above the waterline and close to mid-ship is another way.

Installing a check valve somewhere in the exhaust hose is another.

There are wet mufflers that are supposed to prevent water from back flowing into the engine. The older Verolift wet muffler on our boat did not.

Another good idea, especially for sailboats, is to cross the exhaust hose opposite of which side the engine exhaust manifold is. In other words, if the engine exhaust is on the starboard side, situate the exhaust thru-hull on the port side. This way when the boat is healed over there is less chance of water entering exhaust.

Hopefully, the first sign that you have a hydrolock situation is that the starter clicks but the engine does not crank. Stop right there! You may have a dead battery or you could have water in the cylinders preventing the engine from cranking. If it is hydrolocked, no great damage will be caused by the starter.

If you believe batteries and connections are good, checking for a hydrolock is easy. Open decompression levers and try to hand crank engine. If you see water come out of the air intake, the engine was hydrolocked. In this case, remove injectors and make sure all water is out of cylinders. Lubricate cylinders and change oil and the engine should be fine.

BrianFlanagan and his wife, Tara, cruise the East Coast coast on Scout, their Pearson Invicta yawl

August 2016