We are sailing along in 12-15 knots of easterly wind on a sparkling afternoon on Lake Huron’s Thunder Bay, and I should be ecstatic because I’m finally sailing in a place that has loomed large as legend in my mind for many years.

But I’m not quite feeling it, and it’s not because Bumble Bee, our Catalina 25, is a bit pressed, since we didn’t expect quite this much breeze and we have the big genoa up rather than the jib. And it’s not because there are some waves—in fact, for once the unease in my stomach has nothing to do with this place’s graphic nickname, “Chunder Bay.”

Photo by Wendy Mitman Clarke

Photo by Wendy Mitman ClarkeNo, it has to do with the fact that I’m from Maryland, where the Chesapeake Bay’s summer water temperature approximates beer backwash in a long-forgotten Solo cup, and I’m about to jump into Lake frigging Huron. We’re at 45° North latitude. It’s early July, but I’m betting the ice-out happened just last week.

“I brought you a skin to wear under your shortie,” says Stephanie Gandulla, maritime archaeologist and resource protection coordinator for NOAA’s Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Like everyone else on board, she’s excited to leap off this perfectly good boat as soon as we tie up to the mooring ball that marks the wreck of the William P. Rend.

Launched in 1888, the 287-foot wooden freight barge sank about 1.5 miles off the Thunder Bay River’s mouth at Alpena, Michigan, on September 22, 1917, after arduous years hauling coal, limestone, and iron. As wrecks go around here, her story is not all that glamorous or even spooky—the workhorse was one of the largest of her type on the Great Lakes when she sprang a leak and trundled to the bottom, rather like she’d just had enough already. Everyone made it safely to shore but attempts to refloat her failed.

Today, her football-field length is measured on the surface by two buoys, one denoting the bow, the other the stern—the tallest portion of the wreck, just 6 to 7 feet underwater.

We drop the genoa and Bumble Bee’s owner, Matthew Dunckel, hops up to the bow and snags the mooring ball. I start pulling on my shortie wetsuit, which works great in places like the Bahamas, noting that Stephanie is wearing a full 3mm kit including hat and gloves. Certified to dive to 130 feet through her work with NOAA, Stephanie has approximately 1,000 dives to my three dozen or so. On the other hand, Matthew is about to take the plunge wearing nothing more than shorts and a T-shirt, so maybe I’m unduly worried about early onset hypothermia.

Photo by Wendy Mitman Clarke

Photo by Wendy Mitman ClarkeThe two of them, as well as Don La Barre, a historian with the State of Michigan’s Department of Natural Resources and a serious shipwreck nerd, leap like penguins off the boat while I spit into my mask and engage in a lively internal debate tinged with imposter syndrome—I’ve come all this way, I’ve geeked out with Stephanie for a year now about how long I’ve wanted to sail here and dive on these wrecks, here’s my chance, I have to do it, it’s not even snowing, it’s July for godsakes, I LOVE cold water, what kind of flatlander wimp am I??? etc.—and I climb halfway down Bumble Bee’s ladder, bouncing around now a bit in the waves, shove the snorkel into my mouth, hold my mask in place, and jump.

Perhaps you’ve read about the physiological phenomenon called the gasp reflex. This is an initial response to what’s called cold shock, and according to the National Center for Cold Water Safety, it’s a good thing about that snorkel, since I sucked in air instead of Lake Huron. During the first moments of cold shock, the center’s website notes, “most people find it impossible to get their breathing under control. Breathing problems include gasping, hyperventilation, difficulty holding your breath, and a scary feeling of breathlessness or suffocation.”

I hate it when I’m most people. I especially hate it when I really want to swim over to where Stephanie, Don, and Matthew are cavorting all over the Rend like porpoises, but it’s taking what seems like a very long time to get my fins organized while I remain firmly latched to Bumble Bee’s ladder with one hand, trying not to be alarmed at how hard it is for me to catch my breath.

Eventually, I swim tentatively through the waves toward the wreck site, still thinking more about oxygen choices than maritime history, truth be told. “Right over here!” Stephanie calls to me. “You’ve gotta see these sponges on the wreck, they’re so cool!”

The Rend “invites divers, snorkelers, and paddlers to explore a marvel of naval engineering. Its heavily built wooden sides nearly reach the lake surface, and iron bands that reinforce the massive hull crisscross the wreck,” the description on the sanctuary’s website says. “Near the stern, a boiler is toppled over on its side with other machinery. William P. Rend’s cargo, still within its massive holds, can be seen from the surface.”

It’s been raining a lot around here lately, and Thunder Bay River’s tannin-stained runoff has spilled like Coke all over this part of the bay. By the time I stick my face into the water, I can see about 3 feet. Stephanie points me to a spot, and I make a decidedly half-assed free dive, where I see startling neon-green sponges fixed to the top edges of the Rend. She’s right; they are cool. The rest of the wreck looms just beneath me, and if my lungs didn’t feel the size of walnuts, I’d likely see more.

But it isn’t long before we’re all back on the Bumble Bee, shedding our wet gear, toweling off, and donning sweatshirts. As we leave the Rend and sail southwest across the bay, the tea-colored runoff falls behind, and a nearly tropical blue-green spreads out before us. Don is waxing encylopedic about the Rend and other nearby wrecks. Bumble Bee is sailing smartly now under main and jib. And despite only seeing some cool green sponges and wondering what the heck just happened to my airway, I’m enthralled once again at the history all around us, hidden beneath the water that’s glittering like diamonds in the afternoon light.

Photo by Wendy Mitman Clarke

Photo by Wendy Mitman ClarkeShipwreck Alley

Alpena, Michigan, isn’t a Great Lakes sailing Mecca like Chicago or Grosse Point, but a devoted group of local sailors keep their boats at the tidy, city-operated Alpena Marina, tucked behind a stone breakwater at the mouth of Thunder Bay River, and hit the beer-can buoys on Wednesday nights in summer. Some of them also hop out for local and regional distance races, while others make the trek up and across Lake Huron to cruise the majestic North Channel (see “Northern Light,” April 2024). The Alpena Yacht Club occupies a lovely stretch of bay-front and hosts regular events, and every Tuesday and Thursday evening in summer, the Alpena Youth Sailing Team is duking it out in Ynglings.

It’s a small town—just 10,000 residents—in a rural county. Like many historic waterfront towns, it’s in transition between its industrial past and the future it must shape now that those industries are mostly gone. A little scuffed around the edges, Alpena nevertheless is lively with public art, historic buildings that are being transformed into creative new spaces, great public access to the river and bay, fun eateries, brew pubs, and shops, and a comfortable, easy-energy community vibe.

Tourism is a key element of that present and future, and the Viking Expedition cruise ships that anchor offshore are a big part of that. They began in 2022 with just eight trips; as of this year, the ships visited 26 times. The orange motor lifeboats that beetle passengers to and from the mother ship deliver them right to what is arguably the town’s greatest tourism draw—headquarters of NOAA’s Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary. Located on Thunder Bay River in a repurposed paper mill, it is jointly housed with the Great Lakes Maritime Heritage Center—a terrific, free, interactive museum open year-round—and draws more than 100,000 visitors a year.

Photo by Joe Hoyt/NOAA

Photo by Joe Hoyt/NOAAAlpena’s strategic location on Lake Huron’s western shore—nearly midway on the shipping routes between Lake Michigan to the west, Lake Superior to the north, and Lake Erie to the south—is part of what helped it become a boom town in the mid-1800s. Lumber was the commodity; at its peak, Alpena shipped billions of board feet.

“It is said there was so much lumber [in the river] you could walk from bank to bank without getting your feet wet,” says Brady Kollen, first mate on the tour boat Lady Michigan, noting that Alpena had 17 operating sawmills at one time. Matt Southwell, the Lady Michigan’s captain, adds that “there were reports of ships lined up for 7 miles outside of the river waiting to load lumber.”

Photo mosaic by TBNMS /NOAA

Photo mosaic by TBNMS /NOAAIn 1870, 3,000 schooners worked the Great Lakes. But to get to and from Alpena, those ships had to sail Lake Huron and Thunder Bay, notorious for their weather. Fog, sudden storms, big seas, high winds—all had to be navigated without radar or GPS, and collisions were common.

“A majority of our wrecks list fog as the problem,” says Captain Matt. “The fog is totally unpredictable. It’s really intense, changeable weather. I’ve been doing this for 10 years, and I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve left the mouth of the river on a nice, sunny day and come out here on North Point and the fog just envelopes you, and you can’t see anything.”

Hence, the area’s other nickname—Shipwreck Alley. More than 200 vessels—steamboats, schooners, steel freighters, and more—wrecked in and around Thunder Bay, many near North Point at the bay’s northern edge, where a long, deceptive shoal and cluster of islands with shallows between them was a notorious “ship trap.”

Photo by Joe Hoyt/NOAA

Photo by Joe Hoyt/NOAABecause the water is so cold, prohibiting organisms like wood-eating worms, many of these wrecks are nearly perfectly preserved. And because they comprise generations of commerce, industry, and history, their ghostly presence throughout these waters makes them a singular, otherworldly maritime museum.

In 1981, the State of Michigan created the 290-square-mile Thunder Bay Underwater Preserve. In 2000, the area was expanded and became the Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary; today, it’s 4,300 square miles managed jointly by the state and NOAA. Within the sanctuary are 100 known wrecks, Stephanie says. More than 50 are buoyed so that anyone may tie up, snorkel, paddle, or dive on them. They range from 6 to 310 feet deep, and a map on the sanctuary’s website shows their location and provides details on each.

Map: TBNMS /NOAA

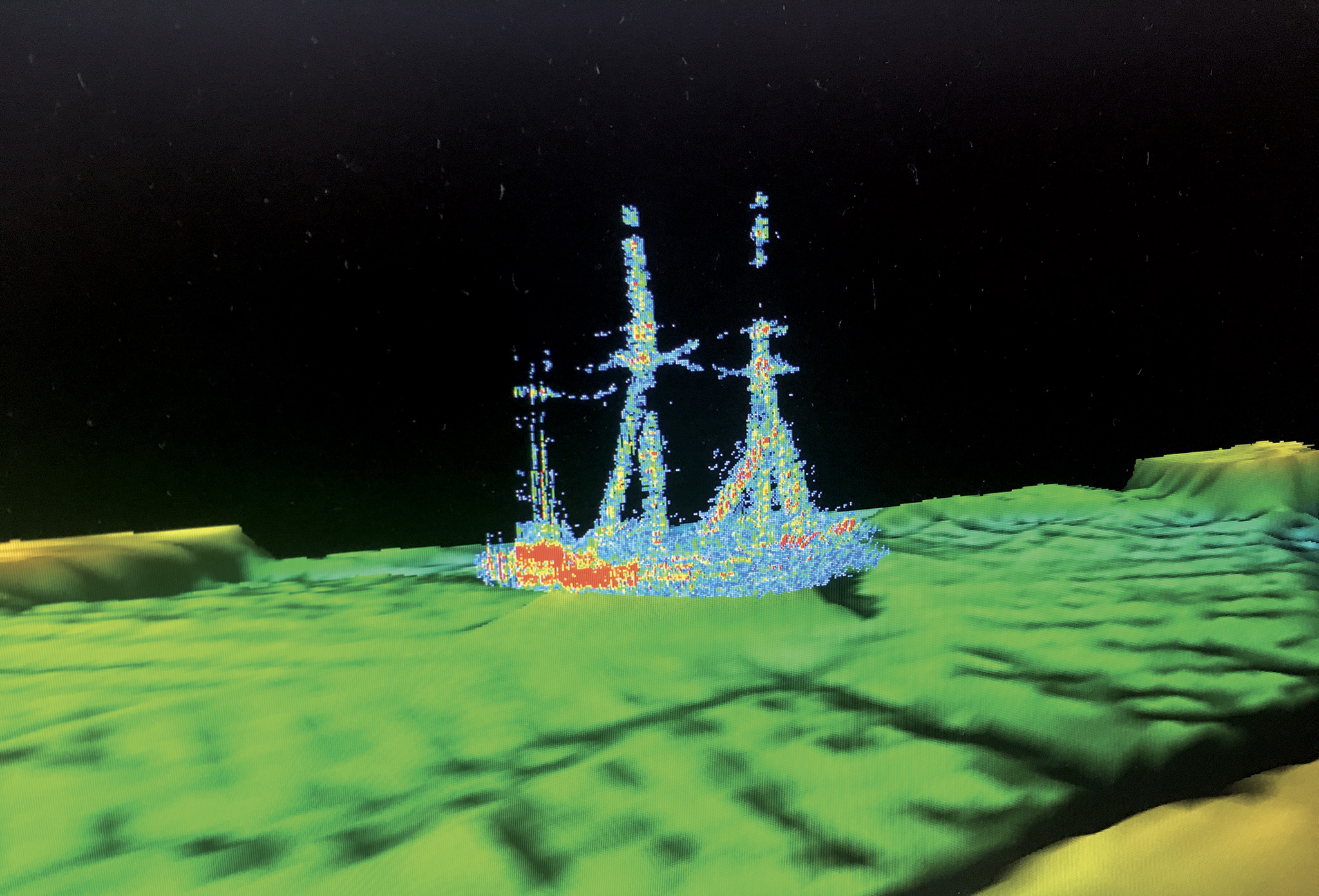

Map: TBNMS /NOAAThe sanctuary is not static. Research is continuous, and more than 100 wrecks have yet to be discovered. Typically they are found through ongoing surveying of the sanctuary’s seabed. When a survey detects an anomaly, researchers will mark the location and then go back and examine it more closely with targeted technology—side scan and multibeam sonar and ROVs, for example—to determine if it is a wreck.

They also know, based on historical research, where some wrecks should be, and that helps guide the discovery process. For example, researchers found the wreck of the Ohio, a 203-foot wooden freighter, in 300 feet of water in 2017 while surveying unmapped seafloor in the sanctuary. The Ohio sank after the 190-foot schooner barge Ironton strayed into its path on the night of September 26, 1894. Everyone aboard the Ohio survived, but five of the Ironton crew perished when they failed to untie the lifeboat’s painter in time and were dragged down with her.

Using the Ohio’s position and extrapolating weather information from the night of the sinking, sanctuary researchers in 2019 refined the search area and, 120 years after she sank, found the Ironton resting upright on the seabed, her three masts and much of her standing rigging still intact. Most haunting of all were images of the ship’s lifeboat, still tied to the transom.

Photo by Ocean Exploration Trust. NOAA

Photo by Ocean Exploration Trust. NOAAWhile many of the sanctuary’s wrecks are “open” to the public, some, like the Ironton, remain off limits with their precise location protected. Along with invasive quagga and zebra mussels, which can colonize and cover wrecks, looting always has been a threat to the historic integrity of such sites, many of which, like the Ironton, are also graves.

A Part of the Community

The morning after snorkeling on the William T. Rend, I hop aboard the Lady Michigan, a 65-foot glass-bottom boat tied up behind the sanctuary HQ, which is how most people lay eyes on some of the wrecks. Today, it’s loaded with passengers from the 660-foot Viking Polaris anchored just offshore, and Capt. Matt says we have a narrow weather window, before an afternoon breeze is expected to build an uncomfortable seastate, to get out to what he calls “the jewel in our crown”—the Monohansett.

The 160-foot-long wooden steam barge, built in 1872, sank on November 23, 1907, while anchored just behind Thunder Bay Island off North Point to avoid a storm. A lantern tipped over and set the vessel on fire, burning so brightly it was visible 14 miles away in Alpena, an event called “the night of the midnight sun.” Crew from the Thunder Bay Island Life Saving Station rescued the ship’s company.

One reason this wreck is exceptional is because its propeller and running gear are still intact. During World War II, First Mate Brady explains, many shallow-water wrecks like this were stripped of their props to be repurposed for the war. Another reason is that it lies close to land in just 18 feet of crystal-clear, blue-green water, so it’s a popular site for people in small boats and snorkelers to visit.

As we approach the buoy denoting its location, Capt. Matt expertly positions the Lady Michigan so that she drifts down over the wreck. The slick formed by the hull’s drift flattens the waves and transforms the water into a looking glass. Standing on deck, I can’t suppress a thrill as the ship’s boilers come clearly into view about 8 feet down, then her propeller, shaft, machinery, and planks and ribs of her hull scattered on the seafloor. On the second drift, I go below to stand over the see-through hull and watch the Monohansett slide by again, seemingly close enough to touch.

Photo by Wendy Mitman Clarke

Photo by Wendy Mitman ClarkeBy the time we return to the river, the flag at Alpena Marina is straight out and waves are smashing the jetty. But back at the sanctuary headquarters, there’s still plenty going on. Tethered to a small floating dock, a handful of Optis and other dinghies bob like a gaggle of ducklings while kids leap riotously into the water—a swim test that’s part of the Alpena Youth Sailing Club, which the sanctuary helps support by providing the location for their summer camps.

About 200 kids per year learn to sail here, says 19-year-old lead instructor River Servia, who himself came through the program and now races for the University of Michigan where he’s studying naval architecture and marine engineering. Once they get older and more experienced, the young sailors are invited to learn keelboat sailing and racing on the Alpena Youth Sailing Team’s fleet of Ynglings.

River says the sanctuary is “super helpful and we’re glad how welcoming they are to us…they allow us to use the [dock] space, and if it’s a rainy day we will use the classroom space they have, and we’ll take the kids and talk about maritime history throughout the sanctuary.”

“It’s wonderful—she loves it,” says Mary Purdy of her daughter, Emma, who is learning to sail this summer. Her son did an underwater adventure program with NOAA and the sanctuary and learned how to diagram artifacts from shipwrecks. “It was right up his alley. It was fantastic. It’s great that these programs are here.”

A few steps away, on the deck beside the marine technician training tank—a 100-foot-wide, 18-foot-deep pool—Daniel Moffatt, a sanctuary education specialist, is wrapping up another “ROV Drop-In”—an afternoon when kids and adults can come and build small, simple, remotely operated vehicles and then pilot them underwater. About 100 people came by today, he says; the sanctuary offers eight such days through the summer. Next year, they’ll be hosting the MATE ROV World Championship, with more than 60 teams from around the country and the world expected to participate.

“Our programs go from pre-school to community college,” says sanctuary Superintendent Jeff Gray. “We try to be more than just a field trip. We try to be embedded in the classroom with assets for teachers and students across the board.” That kind of community engagement, he says, is as much the sanctuary’s mission as research, science, and preservation of Great Lakes history and ecosystems.

“When you come here it’s easy to think of us as a tourist destination, but we do try to think of the community first, and if it’s good for the community members it’s going to be good for the visitors,” he says. “When you look at this campus and all we do here, it’s because we have this community support. I think it’s a pretty cool story in that we’re demonstrating how conservation and preservation can also lead to better quality of life for a community, economic development for a community, and they are seen as an asset versus a tradeoff.”

Photo by Wendy Mitman Clarke

Photo by Wendy Mitman ClarkeI finish the day exploring the Great Lakes Maritime Heritage Center, walking through the eerily canted Western Hope of Alpena—a full-scale replica of a Great Lakes schooner caught in a storm—oodling hundreds of wreck artifacts, and trying my hand at an ROV simulator (getting thoroughly whipped in expertise by a kid who’s maybe 10). At one point, I stop to gaze at the claustrophobic, ponderous gear of a turn-of-the-century hard-hat diver. I take a deep breath, feel pretty good about that shortie wetsuit, and look forward to the next time and the ships still waiting below.

Providing Sanctuary

It’s easy to grasp the cultural and ecological treasures of national parks and monuments like Gettysburg and Yellowstone. But what of the same treasures that lie beneath the water, out of sight and seemingly out of reach? Understanding that such places need the same attention and protections as terrestrial sites, Congress in 1972 passed the National Marine Sanctuaries Act, which authorized the inception of the National Marine Sanctuary System. Today, the system is comprised of 16 national marine sanctuaries and two marine monuments—Rose Atoll and Papahānaumokuākea. Together, they encompass more than 620,000 square miles of waters.

Map courtesy of NOAA

Map courtesy of NOAAIn places like Thunder Bay, Mallows Bay on the Potomac River, and Monitor Marine Sanctuary off Cape Hatteras, the sanctuaries are focused on iconic elements of maritime culture and heritage. In others, such as Stellwagen Bank in Massachusetts, Monterey Bay, the Florida Keys, and Flower Garden Banks off the Gulf Coast, the marine ecosystem and its myriad species are the focus.

“Sanctuary waters provide a secure habitat for species close to extinction and protect historically significant shipwrecks and artifacts,” according to NOAA’s website. “Sanctuaries serve as natural classrooms and laboratories for schoolchildren and researchers alike to promote understanding and stewardship of our oceans. They often are cherished recreational spots for sport fishing and diving and support commercial industries such as tourism, fishing and kelp harvesting.”

With NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries serving as the overarching trustee of the system, the federal agency works with state and local governments and other entities to manage the sanctuaries. To learn more, go to sanctuaries.noaa.gov.

Read more about Ghost Ships: A Ghost Emerges From Sailing’s Past

November/December 2048