Choosing a proper vehicle to tow your boat will reduce wear and tear on your engine and drive train and will minimize the possibility of a major breakdown or collision. A good towing combination won’t guarantee a trouble-free journey, but it will certainly diminish the chances of being stranded on the side of a highway or experiencing a catastrophic accident.

Weighty Matters

Most boat-and-trailer combinations weigh a good deal more than you might think. A trailer alone may weigh a thousand pounds or more, and your boat, ground tackle, engine and other onboard essentials may add another 1,000 or 2,000lb. Our Balboa 26 has a listed displacement of 3,800lb, but under sail it actually weighs close to 6,000lb. Add another 1,000 pounds for the trailer, and we typically end up pulling a little under 7,000lb.

You can find out the full weight of your boat and trailer by stopping at any weigh-station truck stop.In most cases, the operator will be quite happy to help you weigh your rig. You can also check your trailer at a commercial establishment that sells bulk commodities by weight.

If your trailer ball is screwed onto your bumper, make sure that the total weight you plan to tow is well within its specified load limits. Otherwise, you will need to install a separate trailer hitch, typically a “receiver” hitch, in which you insert the actual towing ball into a square-shaped receptacle.

The numbers to pay attention to are the total pulling load, or gross trailer weight (GTW), and the tongue weight, which is the downward pressure the trailer’s tongue places on the towing ball, typically 10-15 percent of the total pulling load. A Class I hitch is rated for 2,000lb gross trailer weight and a 200lb tongue weight. A Class II hitch has a GTW capacity of 3,500lb and is rated for a 350lb tongue weight. A Class IV hitch can handle 500lb of tongue weight and a 5,000lb pulling load. A Class IV hitch can handle 1,000lb of tongue weight while pulling a 10,000lb load.

In addition to having a strong enough hitch, it’s also important to make sure your trailer’s tongue weight meets factory specifications for the rest of your towing vehicle. Too much tongue weight will press down on a vehicle’s rear wheels, lifting its front wheels slightly. This can make steering difficult.

Conversely, too much weight on the back of the trailer will lift the rear wheels of the towing vehicle, which can result in fishtailing and a loss of control when descending steep hills.

Up to the Task

You can check the towing capacity of your towing vehicle by calling a franchised car dealer or searching the web. Most dealerships can interpret axle-ratio codes and other data for you. Thesecodes are often located on the inside of the glove compartment. Good axle ratios—the difference between the pinion and the ring gears in the transmission—for towing can range from 3.2:1 to 4.1:1. My three-quarter ton Chevy has a 4.1:1 ratio, a standard transmission and a 445 cubic inch engine that can generate in excess of 400 horsepower. Still, we sometimes have to gear down when climbing some of the notorious mountain passes for which the Rocky Mountains and West Coast are notorious. Of course, as with any vehicle, we get considerably worse gas mileage when towing—about 12mpg on the highway, compared to 14-17mpg unloaded.

Some trucks and vans come with a factory-installed “towing package.” This will include a receiver hitch that is bolted to the frame; an electrical harness and plug with circuits for both trailer lights and electric brakes; an automatic transmission heat exchanger; a heavy-duty radiator; heavy-duty brakes; a higher gear ratio in the differential, usually 4.1:1; and, in some cases, a sway bar, known as a “stabilizer” or anti-roll bar.

Be aware that any used vehicle with a towing package may have been used hard, especially if it has an automatic transmission and more than 135,000 miles on the odometer. The engine may still be quite serviceable, but most automatic transmissions are likely to wear out somewhere around this time.

Admittedly, I once met a truck dealer who trailered his Ericson 25 from Alberta, Canada, to the Sea of Cortez with a half-ton Chevy, but he understood the mysteries of under-powered towing vehicles and could probably have launched his boat with a golf cart. Most of us are not as gifted.

We used to pull our Balboa 26 with a half-ton Chevy 1500, but we blew the transmission twice—once at the summit of Snoqualmie Pass in Washington and once near the infamous Cajon Pass in California. After the second failure, we overhauled the transmission, sold the rig and replaced it with the three-quarter ton beast we use today.

You may want to go all out and buy a diesel-powered truck. These are capable of towing much heavier loads, although this is rarely a matter of concern when hauling sailboats since they are typically much lighter than powerboats. On the downside, maintaining a diesel truck may be more complicated. While they are more durable, repairs can be very expensive, especially if an injector should go bad.

If your boat is quite heavy, I recommend using a towing vehicle with a long wheelbase. It will track more smoothly and require fewer corrections. The trade-off is that you may have difficulty making lane changes and sharp turns. The road weight of your towing vehicle should also match or exceed the weight of your boat and trailer.That way there is less chance the trailer will take control of the towing vehicle.

Tires and Brakes

If the gross vehicle weight rating of the trailer and its load exceeds 3,000lb, trailer brakes are required by law. To avoid undue sway and backlash, make sure all of your tires (including the spare) are properly inflated to the recommended psi indicated on the sidewall.

The tires on your towing vehicle and all the tires on the trailer should be of the same brand and type. Just because the size specifications written on the sidewall of two different tires are the same, that doesn’t mean their actual size or tread are the same. A kindly neighbor once gave me a five-lug spare that he couldn’t use. It seemed perfect for our boat trailer, but I never checked the load limit. When I blew a tire and replaced it with this “free” spare, I managed maybe a quarter mile before it self-destructed like a birthday balloon. On checking the remnants I found it was a two-ply lightweight tire with a load capacity of about 700lb!

Look carefully at the sidewalls and treads of the tires on both the towing vehicle and trailer. Many trailer tires need to be replaced long before the tread is worn out, due to UV damage suffered by sidewalls when a trailer is stored outside.

Tires on a towing vehicle are also invariably subjected to innumerable potholes and unexpected curbs and bumps, which can crack the casings. Be sure to regularly check for any blemishes in the sidewalls and treads of tires on both the towing vehicle and trailer. These can indicate weak spots in the tire casing and may well lead to a blowout, as we once experience crossing the desert in southern Idaho. Another time, when I happened to notice a large and unwelcome bulge in one of our rear tires, I replaced it on the spot and bought a new spare in Boise. Lesson learned!

Don’t get overconfident if your towing vehicle and trailer have new tires. Young tires can still suffer a blowout, especially out West. Highway pavement gets extremely hot in the summer, especially in the desert, and your tires can become so overheated even the smallest pinhole will expand and possibly explode. The shredded tires you see on the shoulders of highways, particularly in the southwest, are called “alligators” by the professional truckers because they can “bite.”

Electrical Concerns

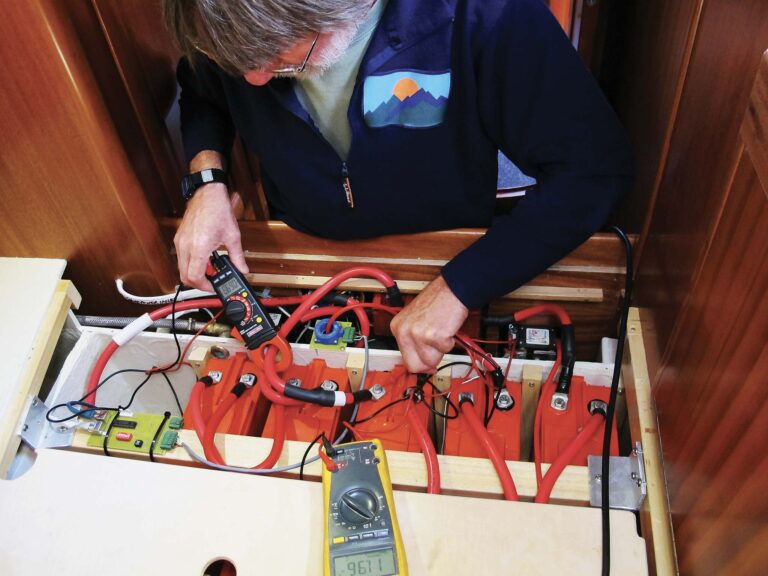

Most problems with electric connections are a result of corrosion, especially if you regularly launch your boat in saltwater. At the start of each season, check your towing vehicle’s entire electrical harness, including the wires for the clearance and marker lights, brake lights, turn signals and electric brake connections. Make sure that they are neither corroded nor dirty. If necessary, clean them with electric cleaner and apply a dab of petroleum jelly to all the connections to protect them from corrosion.

Next, inspect the wiring and lights on your trailer. A trailer’s lights, connections and sockets can easily deteriorate in a single season, so remove all bulbs to make sure that the connections have not rusted and there is a solid contact between the bulb and socket. If you live in a marine environment, you can expect to replace your side lights and tail lights every three or four years.

Your Transmission

Most people prefer an automatic transmission—especially if they live in the city where there is a good deal of stop-and-go driving. However, a six-speed standard transmission is more durable than an automatic and will allow you to tow a much heavier boat and trailer more safely and economically. This may be an important consideration if your boat is a family cruiser.

If you do drive a vehicle with an automatic transmission, you might want to consider installing an additional transmission cooler. These are available at most auto parts stores for a nominal price and are relatively easy to install.

Regardless of the power of your towing vehicle, never exceed 65 mph when your boat is in tow.If your trailer has small wheels, you should understand that 65 mph on standard 15in automobile wheels is the equivalent of 90 to 100 mph on 8in or 12in trailer wheels. There have been plenty of occasions when I’ve seen a boating enthusiast (usually hauling a powerboat!) with a small trailer rip past us at more than 75 mph, not realizing that his trailer—which was hidden behind his camper—was bounding port and starboard like a roped calf.

Other Concerns

If towing with an automatic transmission, do not use overdrive, because the overdrive gear is very small and is not designed to carry a load. It also important to realize that altitude affects engine efficiency, with a loss 3-4 percent in power for every 1,000ft of elevation—that amounts to a 40 percent decrease when crawling through the 10,000ft mountain passes we have here in Colorado.

There is also a trade-off between summer heat and mountain roads. A transmission—especially an automatic unit—running at high speed in the lower gears can heat up quickly. But it is also true that most engines can overheat if there is an insufficient amount of air blowing through the radiator, as when plodding up a long hill at a snail’s pace.

Going downhill, use your gears and engine, not the brakes, to keep your speed under control, regardless of the size of your engine and your transmission (although engine braking can easily can easily heat up an automatic transmission). If you must use your brakes, depress the pedal at regular intervals to gradually slow your vehicle speed to 5 mph below the speed you want. The process may take up to 25 seconds to complete, but when you reach that point, take your foot off the brake pedal and use the lower gears to maintain a safe speed.