One challenge with older boats that have been out of production for decades is obtaining replacements for components that may have been custom-made back in the day. Good luck finding a new bow pulpit for your 1974 Flexiflyer 43 or a mast cap for the rig on your 1967 Brickouthouse 29. Or, for that matter, drop-in replacement portlights for many of the thousands of boats built by long-defunct yards.

From the 1980s onwards, most production boats were equipped with off-the-shelf portlights from one of a handful of manufacturers—for example Lewmar, Moonlight, Goiot and Bomar—and replacements for these are not hard to obtain, as long as they are still in the maker’s catalog. It’s the owners of boats created by builders and stylists who specified interestingly shaped custom ports who find themselves being cursed 20, 30 or 40 years later.

Sooner or later, all portlights leak. The lenses also craze or crack and become so cloudy you can’t see through them anymore. If you manage to remove a leaky portlight without damaging its trim, you can usually rebed it with sealant and heave a sigh of relief—but eventually, there may be no alternative but to replace it.

Many owners of older boats that don’t carry much value on the brokerage market choose the most cost-effective replacement option, which is to ditch their framed portlights and make new surface-mounted ones out of plexiglass. Screw these to the hull sides with a bit of sealant and you’re all set—right? Well, maybe. It’s not as easy as it sounds. More to the point, if you’re fond of the way your boat looks, its appearance can be drastically altered by a different style of portlight—and it is seldom improved by merely screwing on a few pieces of plastic. Still, if appearance isn’t high on your list, then properly specified and installed surface-mounted portlights will certainly keep the water out. Many boats from the ‘80s and later were fitted with frameless portlights recessed into the hull, and it’s certainly possible to replace these without detracting from your boat’s appearance.

If you’re not scared to take a power tool to your pride and joy, it’s often possible to enlarge a cutout to install a bigger or differently shaped off-the-shelf portlight. It’s a job that’s well within the ability of the average do-it-yourself. But again, this can radically alter your boat’s look, so think about it carefully.

What if you’ve found a great deal on portlights that are just a bit too small? You could fill in the existing apertures with plywood or foam skinned with fiberglass, or with solid fiberglass sheet such as the G10 sold by McMaster Carr and other online outlets, and then cut new holes for portlights. Be warned, though, that this is nowhere near as easy as enlarging an existing hole and will lead to a great deal of finish work.

An easier option is to have the new portlights custom-made to fit the existing apertures. Companies like Bomon and Vetus-Maxwell will all make framed portlights to any specification. All you have to do is create templates of the openings, measure the thickness of the cabintop sides and specify the type of frame and interior trim. It’s not inexpensive, but the cost is not much higher than off-the-shelf portlights, especially when you factor in ease of installation.

But perhaps you’re thinking that there’s still life in your existing portlights. In that case, you need to read Don Casey’s guide to portlight repair in a future issue of SAIL magazine.

Case Study: Installing custom-made Vetus portlights on a 1970s cruiser

1. Many years ago, a previous owner had replaced the fixed ports on this 1973 boat with homemade surface-mounted acrylic sheet. Now they were so clouded you couldn’t see out.

1a. Step one was to make templates of the portlights. I traced the outlines of the insides of the cutouts onto paper and sent them off to Vetus. Later, I would wish I had made proper cardboard templates and tried them for size!

2. After removing the screws, we carefully prised off the portlights.

3. They had been bedded in silicon, which we scraped off with a sharp chisel.

4. Next, the screw holes were filled in with thick epoxy resin.

5. The Vetus Marex “comfort” ports have a ribbed, flexible gasket inside the outer aluminum flange, which means you don’t need to bed them in sealant. This makes for a cleaner, faster job. The interior flange fits inside the cabintop cutout, and the interior frame is screwed to it—no need to screw through the cabintop. They also have toughened glass lenses instead of the usual acrylic or polycarbonate.

6. The interior frame comes in one or two pieces, depending on the size of the portlight.

7. Oops. I had been a bit sloppy with my pattern making, which meant a couple of apertures had to be enlarged slightly. This is when we found out that my trusty Dremel would work just fine via my 150-watt West Marine plug-in inverter.

7a. If you have to do this, tape a plastic bag to the inside of the boat to collect the dust.

8. Offering up the portlight—note the thickness of the sealing strip.

9. Tightening the screws opposite each other ensures even clamping to draw the two halves of the frame snugly against each other.

10. A plastic strip is supplied to conceal the screws.

11. The new ports immeasurably improve the look of this 1970s classic—and it’s great to be able to see out again. What’s more, they haven’t leaked a drop! If you do a good job with your pattern making, installing these ports is a breeze.

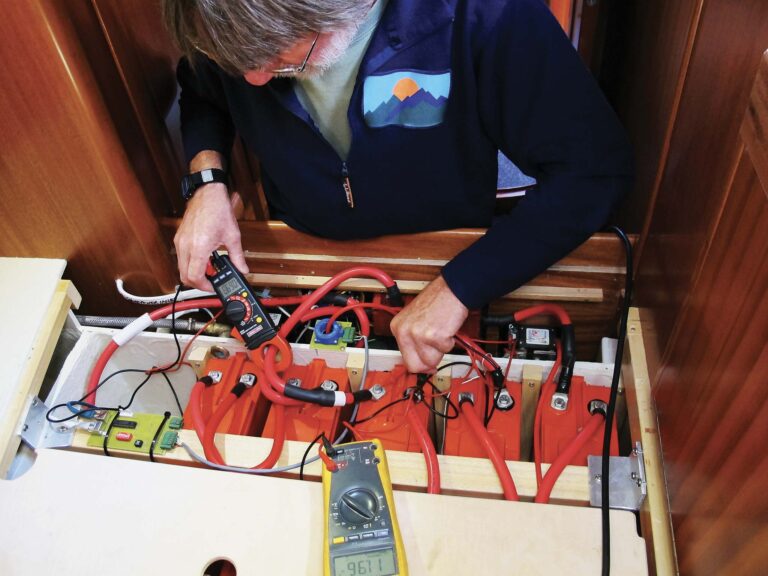

Photos by Peter Nielsen