It could have been the sound of a bird, or maybe the wave pattern changed? Was it the sun hitting my cheek through the portlight? Something startled me out of a deep sleep. What time was it?

I had just slept three hours past my alarm: hard asleep for four and a half hours. This wouldn’t have been an issue if I were anchored in some cozy harbor, but I was in the North Atlantic single-handing. At least there weren’t rocks to hit, but the sides of those container ships aren’t exactly soft. A quick look around showed no sign of anything except ocean and sky. The waves had settled, the sails only needed minor adjustments, and the windvane autopilot was holding course.

I had been fighting some tough weather through the night and the preceding days. Sail changes and reefing were frequent, conditions below deck were poor for sleep, and I had clearly exhausted myself. Heaving-to for some earlier rest would have been smart, but I was younger and overly ambitious, pushing myself against nothing but trivial goals I set for myself.

We think nothing of the importance of maintaining a boat to keep it seaworthy. Well, what about maintaining our bodies? Among proper nourishment, physical fitness, and a sound mind, adequate rest should rise to the top of our personal maintenance checklist.

You want to remember your passage, right? Without sleep, that isn’t going to happen. Memories won’t be transferred from our short-term to long-term storage. The brain creates new pathways for this information but needs us to be asleep to complete the work. If we deprive our bodies of that opportunity, our logbooks and photos will be our only reminders of that time at sea.

Sleep deprivation also pushes us to make impulsive decisions. We rely on less evidence to draw our conclusions because our short-term, or working memory, is also impaired. We struggle to process verbal communication, and fail to properly reason, focus, and learn. We simply cannot extract all the information available to make the best judgment calls, and it puts us on a riskier path. The same becomes true for how we treat our crewmates: in tight spaces, it’s easy for irritability to escalate situations.

Sleep drives our physical performance too: fine motor functions, strength, stamina, balance, and reaction time. Even blood pressure and immune systems are affected. Tasks such as trimming sails, steering, or even moving about the boat become more challenging without adequate rest. These symptoms create situations that can quickly become even worse problems, like going overboard or a physical injury.

There is no catching up on sleep. Once it’s missed, the benefits are gone. However, it’s never too late to benefit going forward. Whenever there’s an opportunity to rest on a passage, take it. Conditions can quickly arise that make it challenging to sleep. Chasing subtle noises throughout a quiet cabin in light air can be just as disturbing as the jostling effects of falling off the back side of waves in rough conditions.

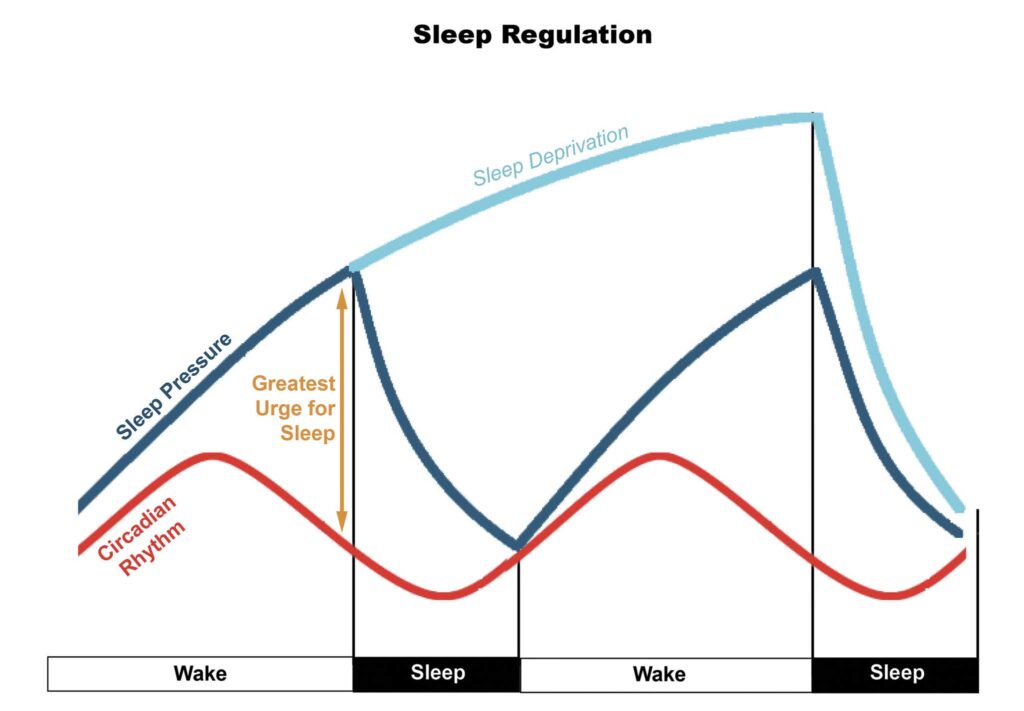

On land, we all typically sleep for one extended period and remain awake for the rest of the day. Our bodies are trained and have evolved to function in this manner. There are two factors driving this sleep pattern: sleep pressure and our circadian rhythm.

Sleep pressure is what makes us feel tired after extended periods of being awake. Chemicals, such as adenosine, build up and block portions of the brain assigned with wakefulness and activate the sleep promoting regions. It is only after sleep that this chemical-driven sleep pressure drops, and our minds can feel refreshed. Even if consuming caffeine, these chemicals continue to build—caffeine only blocks the receptors for these chemicals. That’s why we feel even more tired after the effects of caffeine wear off.

Circadian rhythm is our internal clock—a natural 24ish-hour cycle that allows our bodies to carry out essential functions and processes. Our circadian rhythm is responsible for promoting wakefulness during the day, externally cued by sunlight, while also inducing sleep through the production of melatonin.

Cross these human traits with passage making or distance racing, which requires constant vigilance, and there’s a dilemma. Let’s also factor in that focus deteriorates on deck after as little as 20 minutes and considerably after four hours. The best compromise we’ve developed is a watch schedule.

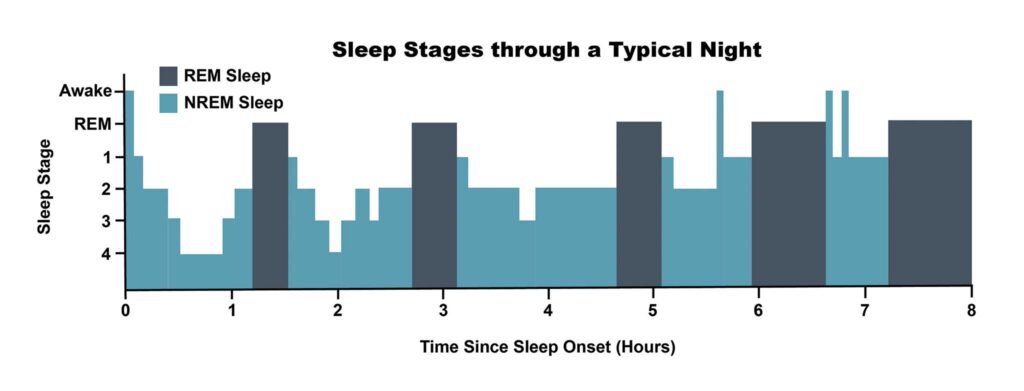

When we first fall asleep, our brains shift to slow wave activity and a phase known as NREM (non-rapid eye movement) sleep. We transition through several stages of this, with each one bringing us deeper into sleep and harder to wake. After around 75 minutes we enter our first stage of REM (rapid eye movement) sleep. Our bodies are in a state of unique paralysis during this stage, and we experience dreams. In a full night’s sleep, we then transition back into NREM sleep and complete around five cycles. As time progresses, the NREM portion of sleep becomes shallower in depth, and REM sleep takes over a longer portion of each cycle.

The key takeaway is that each initial NREM stage takes about 20 minutes and a cycle of NREM and REM sleep takes approximately 90 minutes. We can use this science to optimize our sailing experience: to avoid waking up disoriented and groggy from a deep NREM stage, we should either wake up after 20 minutes of sleep or allow a 90-minute sleep cycle (or increments of).

Without REM sleep, hallucinations can occur, among other deficiencies. So, it’s important that we achieve enough REM sleep by including those 90-minute naps. If you find yourself conversing with dolphins, it is more than time for a longer nap.

When single-handing offshore, I set my alarms for either 25 minutes or 95 minutes, situationally dependent, allowing myself a few minutes to fall asleep. This schedule allows me to check my surroundings frequently yet still get the rest I need.

Double-handing, with someone always on watch, there’s the opportunity for multiple sleep cycles in an off watch. I’ve found four-hour watches to be the most successful. It provides time for the off watch to eat, undress and dress, tend to the log, navigate, and get in two 90-minute sleep cycles. When conditions deteriorate, two- or three-hour watches can be more effective at maintaining focus on deck (this does sacrifice some sleep and emphasizes the need to get more rest during the daylight hours).

While it’s more challenging to sleep during the daytime, when off watch, your job is to rest. You might not get the chance later.

A fully crewed vessel can have a luxurious watch schedule. I prefer three watches, with each on deck for two to three hours. This means two hours on and four hours off, or three hours on and six hours off. The off watch can get a continuous two or three sleep cycles between time on watch. In this arrangement, the next watch is on-call in case assistance is needed. However, that’s rare in a cruising situation. Forward thinking encourages reefing and sail changes early, before it becomes an emergency. Two watches, alternating every four hours, is a suitable alternative, depending on collective experience, but not as restful. I don’t recommend a rolling watch system, as it means there is regular disruption below deck and prevents the off watch from getting continuous rest.

The sleep cycle times mentioned earlier are averages. Your body may prefer times that are slightly shorter or longer—you will need to experiment to find what works best. Maintaining a polyphasic sleep plan (as opposed to a full night of sleep), is not equivalent to our natural approach. However, it does combat many of the issues associated with sleep deprivation.

I regularly find myself tired the second day into almost any passage. The first day comes with the adrenaline of starting a new adventure, and it is tough to fall asleep, leading me into a deficit almost immediately. If conditions are fair, my body finds a new rhythm after a few days, and I reach a point where I feel as if I could continue in that pattern forever. I’m typically in my bunk much more than eight hours in this case, more like 10-12 hours, to answer my body’s call for rest.

Do yourself the favor as early as possible: stop anything inside the boat and on deck from rattling, rolling, and banging—it will eventually wake you up again. If you are on watch, always think about how you could help the off-watch crew sleep better. This may be as simple as connecting a boom preventer when sailing upwind in light air and rolling seas. Skip the coffee and energy drinks, they only mask the problem and make it hard to fall asleep when there’s an opportunity.

Smart sleep habits lead to enjoyable and safe passages. Sleep is a key ingredient to core functionality, including memory, decision-making, coordination, and health. Plus, it just feels great to be well-rested.

November/December 2025